LA PLAZA NIGHTMARE

Gabrieleños struggle for recognition, face challenges

By Bethania Palma Markus, Staff Writer

Posted: 01/30/2011 06:06:59 PM PST

Ernest Tautimies Salas holds historical family photos in Covina, Thursday, January 27, 2011. They are direct descendants of Southern California's original people, the Gabrielino Indians who have California recognition but are struggling to get federal recognition. (SGVN/Staff Photo by Eric Reed)

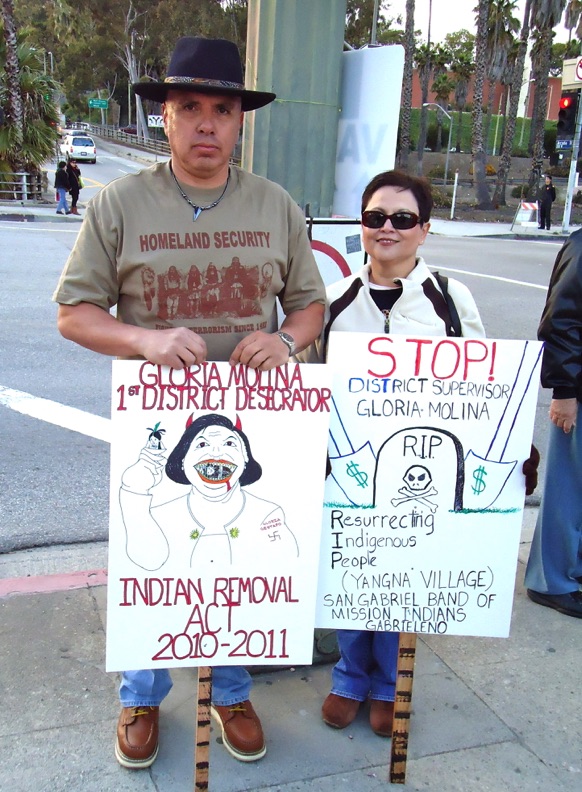

When Gabrielino Indian Ernie Salas recently voiced concerns about the unearthing of ancestral bones during a construction project near Olvera Street, the builder of the Mexican cultural center said he heard Salas and his relatives were not "real Indians."

Salas can trace his lineage back to the first California inhabitants that built the state's Catholic missions. But Gabrielinos aren't recognized by the federal government.

And, if you ask any of the four groups claiming to be the legitimate leaders of the Gabrielinos, they will each claim to be the legitimate representatives of their people.

So it goes for what remains of Southern California's indigenous people.

Salas' son, Andy Salas, 42, of Covina, is pushing to gain federal recognition and preserve what remains of the Gabrielino heritage. But he's not alone. There are a handful of groups working separately toward the same thing.

"I just want the culture to be preserved for my kids and their kids and their kids to come so they can see where they come from," Andy Salas said. "Maybe we could get a little piece of land where we could put a cultural center and maybe some windmills and generate revenue for everybody."

Archaeologist Gary Stickel backs Salas.

"His group is legitimate - they can trace their ancestry back to the San Gabriel Mission records, to the actual villages their ancestors came from," he said. "In a humanistic way, I found this group of Gabrielinos behave with the utmost integrity and nobility. They have no ulterior motives."

Officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not return several messages left over the past two weeks.

But records show that four groups using the Gabrielino name have applied for recognition.

The BIA lists seven criteria for becoming federally recognized, but most of them include that the group show a common identity and a common governance - traits the Gabrielinos don't have.

The tribe began splintering after a large faction partnered with Santa Monica-based attorney Jonathan Stein about a decade ago in hopes of winning rights to build and run a casino in the Los Angeles area.

Stein said his group's membership is 1,688 strong.

"You got 2,000 people who are completely unified saying let's go get it, then you have these little fringe groups of ego centered personalities who say, `What I want is more important than what 2,000 people want,"' Stein said. "That's why they're on their own."

He estimates there are about 2,500 living Gabrielinos.

Bernie Acunas, a tribal councilman in the group allied with Stein, said the situation is far from ideal.

Like most of the L.A. area's first inhabitants and settlers, the Gabrielinos who survive today are blood relatives. Acunas, who now lives near San Diego, is Andy Salas' cousin.

"It's a terrible family thing to be honest with you," said Acunas, a Gabrielino who grew up in San Gabriel. "I wish we'd all stayed together and got one thing accomplished at a time. Everyone is trying to do different things and it makes things hard."

But the culture dwindles with every generation and some said this could be a last chance to save it.

"This is a really crucial time that the Gabrielinos need to work on recognition as a tribe, not as a casino," said Ron Andrade, executive director for the L.A. City and County Native American Commission.

Andrade backs a group lead by Anthony Morales, who didn't return phone calls seeking comment. Morales, whose group is based in San Gabriel, opposes gaming.

He is also related to Andy and Ernie Salas.

"The problem is in L.A. County it's been totally based in greed," Andrade said of efforts to open a casino. "Anthony's (group) is based in religion and culture. He's very active in all the varying (cultural) aspects."

Federal recognition gives tribes sovereignty and provides protection for the culture and language, Andrade said.

"It's extremely important that they get federally recognized so they can have these protections," he said.

Because contact between the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers was intense and often brutally oppressive, much of the Gabrielino culture and language has been lost over time, said Lowell Bean, an anthropologist who is an authority on California Indians.

When the Spanish came in the late 1700s, California natives were "missionized," Bean said. They were taken from their homes to build and work at the missions. The Gabrielinos are named for the first L.A. mission - Mission San Gabriel Arcangel.

Under Mexicans and later Americans, the Gabrielino culture was all but obliterated, experts said. Being an Indian was stigmatized. Many were killed.

"There are very few fluent speakers of any of the California languages," Bean said. "Indians weren't allowed to speak their language - they were sent to schools where teachers would punish them if they spoke their language."

Matt Teutimez, a Gabrielino from Cypress, agreed.

"My great grandfather knew you could get killed by stating you were Indian," he said. "My grandfather said he was Mexican when he needed work. That's what a lot of families did - they integrated themselves."

They learned Spanish and English and took Spanish surnames, he said.

But younger Gabrielinos are trying to revive the culture and language and hope getting federal recognition helps.

Teutimez said the majority of Gabrielino language is written down and there are recordings of it.

And while developers in places like Playa Vista, Long Beach and downtown Los Angeles have been digging up native remains for years, Gabrielinos don't have a place to bury their ancestors in peace.

Federal law dictates the remains of Indians be returned to their descendants for burial.

"With the Gabrielinos, there are some remains that are ready to be repatriated but they have no land, so they have no place to repatriate them," said Eugene Ruyle, a retired anthropology professor at Cal State Long Beach who helped Native Americans fight development of a strip mall on a sacred site. "It's a long process and I'm sure it's very painful for a lot of Native Americans that want to see their ancestors treated with respect."

April 28, 2012

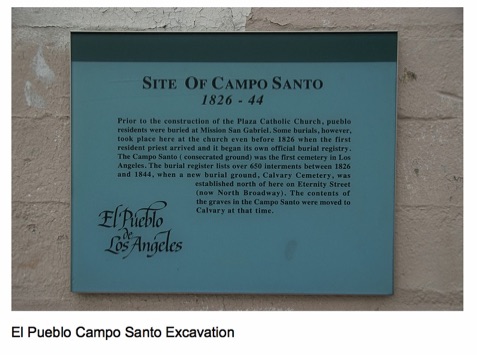

Los Angeles County officials were justifiably criticized for the rushed and, at least initially, haphazard manner in which they excavated the historic remains discovered when construction crews working on La Plaza de Cultura y Artes accidentally struck the vestiges of a 19th century cemetery. The earth under the courtyard of the new downtown museum, dedicated to Mexican and Mexican American heritage, yielded the bones and artifacts of more than 100 people.

They were most likely a mix of Mexican, Spanish, European, African and Indian settlers who had been buried in a Catholic cemetery. Historical records indicate that the cemetery and its graves were moved in 1844 to another location. Apparently, not all the remains went along. The inventory of what was dug up is stunning and horrifying at the same time: almost complete skeletons, skulls, jaws and teeth, fragments of coffins, metal crucifixes, rosary beads.

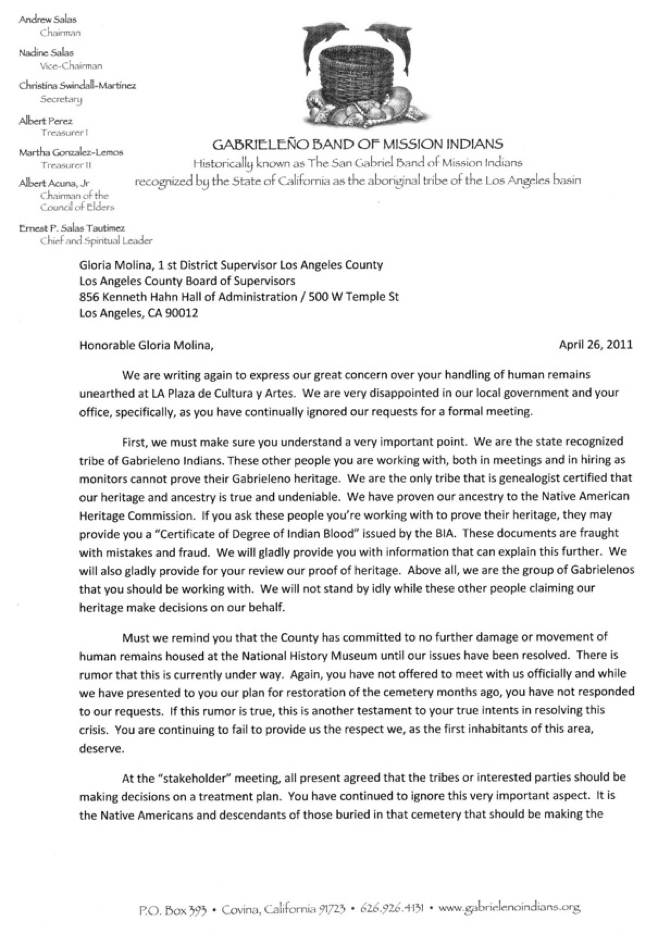

County officials made a number of mistakes at the outset, the biggest of which was that they didn't immediately stop the excavation work when they struck the cemetery to consult with historians and descendants of the dead about how to proceed. In the aftermath of their initial blunders, however, they have been more meticulous about the process of reassembly and reburial. They notified likely descendants by reaching out to numerous cultural groups, including dozens of Native American tribes, and consulting with many of them. As required by U.S. law when dealing with Indian remains, they found a federally recognized tribe, the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians, to assist officially.

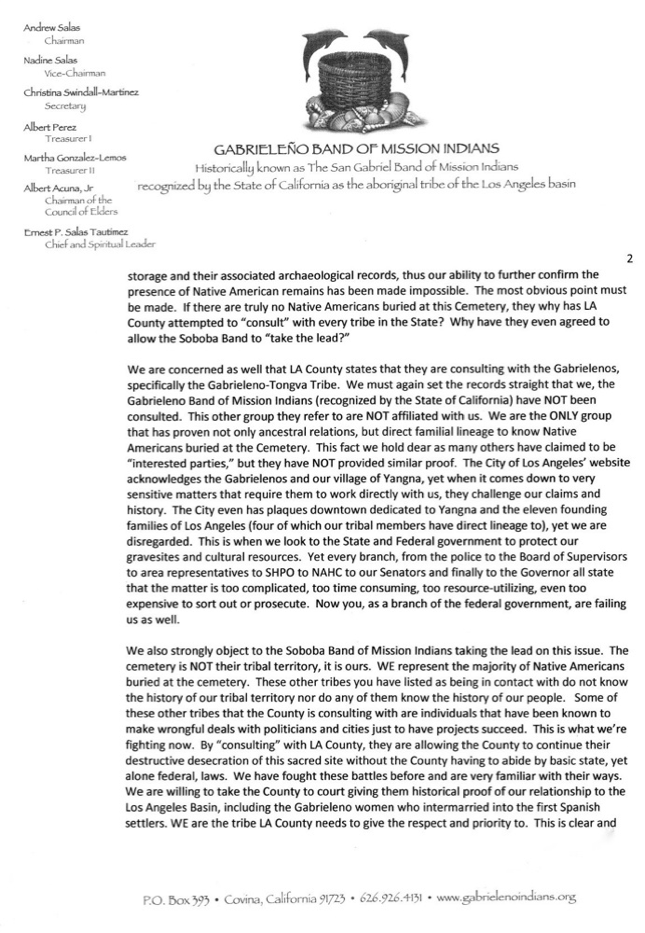

Still, the process has been fraught. One of the tribes that has been watching the county's actions fears that the initial excavation was so careless that consultants hired to do the reassembly couldn't possibly avoid commingling remains. "We feel like you might as well make a mass burial in a large hole," Christina Swindall, secretary of the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians, wrote to county officials.

No DNA testing of the remains was performed, at the request of descendants who wanted to avoid further disturbance of the bones, according to county officials. Because the cultural heritage — let alone individual identities — of the remains could not be positively determined without DNA tests, theU.S. Department of the Interior ruled that the county was not subject to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. But no one involved in this predicament doubts that the remains included some Native Americans. The county has hewed to California statutes governing Native American reburials.

Reassembly of the remains was carried out at the Pomona Fairplex under the watch of representatives of descendants and a monitor chosen by the Soboba Band. Each set of remains and associated goods was put in a cotton bag, then placed in a custom-made birchwood box. Between April 16 and April 20, the boxes were interred.

It is not clear how successful workers were at keeping individuals' remains separate, or how carefully workers and archaeologists at the site documented their original locations. Some eyewitness accounts of the excavation make us skeptical that county officials can be sure they have reburied the sets of remains in the spots from which they were extracted, as the groups consulted wanted them to be.

What was most important for history and for the peace of mind of descendants is that the remains be reburied under the grounds of

La Plaza and memorialized with the dignity and deliberation they were not accorded when they were initially unearthed. And the county appears to be doing that as best it can. Any descendants who wanted to witness the reinterment were allowed. A fence around the site obstructed viewing by curious passers-by. "There will always be questions," said Rose Ramirez of Los Pobladores 200, a group that traces its ancestry to the settlers of Los Angeles. "But we're getting what we wanted right now — reburial."

Los Pobladores will hold a memorial Mass, probably in May. County officials have pledged to allow all groups claiming ancestors to hold ceremonies at the site.

We expect them to follow through on that, even if it means 100 ceremonies over 100 days.

Copyright © 2012, Los Angeles Times

From: Christina Swindall

Sent: Wednesday, April 25, 2012 11:34 AM

To: Dawn McDivitt; gherrera@lapca.org

Subject: Treatment of Gabrielenos by La Plaza staff

Dear Mrs. McDivitt and Mr. Herrera,

Please find below two videos of the treatment we and the photographer of the LA Times received while on public property in front of LA Plaza Monday night. Let me know if you have technical difficulties - we're figuring out how to send videos by email. I was asked to meet the photographer in front of LA Plaza to get photographs of myself for an upcoming article in the Times for which I believe both of you were interviewed for as well. The security staff began harrassing us and I began recording the event. The treatment is another reflection of how the County and Museum have treated us all along. The harrassing behavior of these employees needs to be evaluated. If they worked for me, I'd fire them. The amount of "east LA" attitude and profanities was uncalled for. Even the photographer stated that in 14 years as a photographer, he had never been treated so badly.

Christina Swindall, secretary

Gabrieleno Band of Mission Indians

Dear Christina,

On behalf of LA Plaza, I apologize for the inappropriate response as recorded by your videos. We have reached out to Securitas, the Security Company we hire, and I’ve required they retrain each and every one of the security on staff.

All of last week, the security on staff was instructed to monitor the temporary fencing surrounding the cemetery. We did so to ensure the process continued in a private and respectful manner. However now that the reburial is complete, there is no reason for this continued process and unfortunately that word was not conveyed to the staff on-site. We’ve taken steps to rectify this.

I’ve contacted the LA Times to tell them they can return and we will not prevent them from taking photos from the public sidewalk.

My apologies once again,

More on La Plaza

Rest in Peace: Ancestors Finally Return to El Pueblo

The excavations were appalling and horrific. The county excavated 27 "almost complete adult skeletons," 4 "almost complete burials," 74 other sets of "human remains," including skulls that could not be pieced together into complete skeletons or burials, and 82 sets of "associated funerary objects" such as pieces of coffins, crucifixes and beads, according to the county's own draft inventory obtained under a public records request. The remains were carted around the county in over 315 bags, 16 buckets, 7 boxes and 2 jackets.

Brian McMahon, the Director of the Cemeteries Department for the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles wrote to project officials on January 11, 2011: "Frankly, I was surprised and disappointed to learn through a story in yesterdays' Los Angeles Times that a substantial number of remains had been discovered and unearthed at your construction site. In your only communication with me about the discovery of the remains last November, the impression I received was that a few bone fragments were all that had been found, and that a few more might be found during the course of the project." Again, "our original impression was that there would be relatively few fragmentary remains." Mr. McMahon emphasized: "That you have possibly discovered substantial remains, including full burials, obviously goes way beyond the scope of my Nov. 17 letter to you, and raises for us a number of new ethical and legal questions concerning the current activity at your construction site."

El Pueblo Plaza Church Cemetery Excavation January 7, 2011 | Courtesy of The City Project

Why didn't the county stop until January 14? County Supervisor Gloria Molina did not want any publicity that would delay the April 9, 2011, grand opening of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, whose mission is to celebrate Mexican and Mexican American culture.(The center is an official project of the county and the county CEO is the official project manager, although the project has nominal non-profit status.) An investigator for the county coroner recorded in her case notes when remains were first excavated on October 28, 2011: "Today, approximately 15 small fragmented human bones and teeth were unearthed by a back hoe, after it began digging below undisturbed top soil." The executive director for the project, Miguel Angel Corzo, told the investigator that "Molina is out of town for a few days but does not want media attention drawn to this project until its opening."

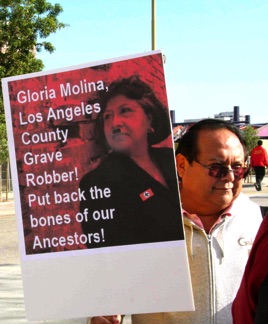

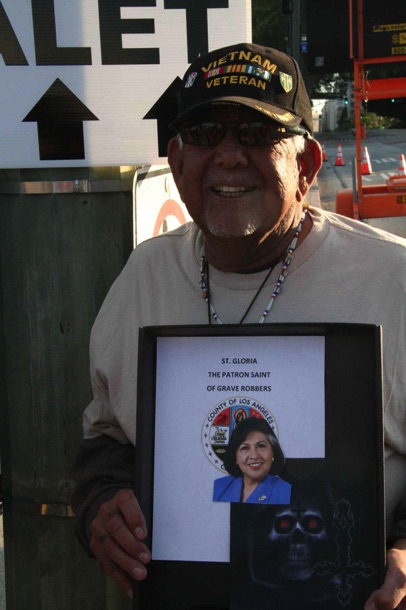

Christina Swindall-Martinez, secretary for the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians whose Ancestors are buried at the site, told the Associated Press that tribe members pleaded with museum and county officials to delay the opening until an agreement could be reached on reburial of the remains and restoration of the cemetery. "She said members felt particularly affronted by Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina, who has long championed the project, serves on its board and was scheduled to be honored at the gala."

Prof. Paul Langenwalter testified before the Native American Heritage Commission in March 2011 that human remains were removed piecemeal; legs, skulls, and beads were separated; accepted archeological practices were not followed; and the supervisor's office put undue pressure to keep going despite the unearthing of the remains. Prof. Langenwalter testified that there was reason to believe the remains and artifacts included Native American remains and artifacts. He pulled his archeology students from the site after a few days rather than associate them and Biola University with the devastation. Click here to read Prof. Langenwalter's testimony.

Archeologist Monica Strauss testified at the same hearing that she was "flabbergasted" by the way human remains were unearthed because conventional archeological practices were not followed. Click here to read Ms. Strauss's testimony.

Elizabeth Miller, an anthropologist and osteologist at Cal State L.A., told the L.A. Weekly that the environmental impact report prepared for the county by the Sanberg Group Inc., which should have provided enough information to guard against the excavations, was "incredibly poorly done. I do not see how you can do a legitimate assessment of a site where you know there was supposed to be a cemetery at one time, and not find any trace of the over 100 individuals that ended up being excavated." She added: "I'm completely at a loss."

But Miller's own actions raise an eyebrow. Miller worked with Sanberg to move the remains, seek funding and study them. After Sanberg apparently moved the remains from the burial site to their own offices in Whittier, Miller moved the remains to Cal State L.A. and sought over 20,000 in funding to do research on them. When the university president found out, he directed that they be removed because having the remains on campus was against university policy, according to public records obtained from Cal State L.A. The remains were then moved again to the County Museum of Natural History in bags, buckets and boxes on January 25 and February 3, 2011.

Gloria Molina told a hearing by the Native American Heritage Commission in March 2011, "it truly pains me that this . . . has unfolded in this manner and in this way. And I'm truly sorry for it," according to the L.A. Times. "We took their word," referring to Sapphos, which prepared the environmental impact report. "Had they done better work, we wouldn't be in this situation." According to L.A. Weekly, Molina admitted: "There's probably gonna be plenty of blame to go around on all of it. For us, we probably didn't have as thorough an EIR as we probably should have had."

The county continued to retain Sapphos to handle the repatriation process despite the fact that their flawed EIR created an apparent conflict of interest. A Los Angeles Times editorial called on the county to retain a professional mediator, but the county refused. The county refused to allow Native Americans to visit the excavated burial site to honor their ancestors unless they signed agreements to work for Sapphos. The county refused to allow descendants to visit the remains at the Natural History Museum unless they waived all claims arising from the excavations.

To its credit, the National Park Service (NPS) has worked to protect the remains and the descendants. NPS notified the county by email on February 15, 2011, that NPS had just learned about the uncovering of the cemetery and was withholding federal grant funds until the issue was resolved. NPS followed up with a letter on March 24, 2011, directing the county to consult with all concerned parties to ensure historic properties were protected under section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. NPS withheld 04,209.64 from a 97,058 grant to the county issued, ironically, to "Save America's Treasures" program. The project instead has devastated Americas' treasures at El Pueblo. Los Angeles Plaza Historical District is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The federal process nevertheless has not been a model of democratic engagement based on full and fair information. The process has been confusing, inconsistent, and incomplete. The real consultations, decision making and work takes place with federal staff. Indeed, NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repartriation Act) staff told the review committee on November 8: "staff functions . . . nationally [are] where all of the real consultation and decision making is done . . . between museums and Federal agencies and the tribes, where the actual NAGPRA work comes." The investigation, reassembly and reburial process here has involved federal staff working closely with county and project representatives. The federal staff generally has not consulted with the Native Americans and descendants of the Pobladores themselves.

The committee nevertheless voted as follows on November 8: "In this instance, as the same treatment and disposition is agreeable to all Native and non Native parties concerned [sic], . . . the Review Committee conclude[s] that it cannot make a determination whether the remains are Native American or not; second, that we believe that Los Angeles County may therefore proceed under other law; and third, that we request that the Secretary's letter reflect this view." NPS sent a follow up letter to the county on December 9, 2012.

Sound confusing? It is. The California Native American Heritage Commission itself wrote to NPS that "NAHC is confused" by NPS's actions.

The excavations of the human remains was a travesty. The consultation process was haphazard. The county has not yet released other records that would demonstrate whether the reassembly and reburials were any better. Record requests are pending. The county's description of what it claims happened is a paragon of banal bureaucratic prose that masks the truth of what really happened.

To date, no one has been held responsible and accountable for the excavations to deter others. U.S. Air Force officials were recently disciplined for losing the body parts of two service members, according to the New York Times. Although the loss of the two body parts "equates to an aggregate success rate slightly greater than 99.9 percent" based on thousands of remains and body parts at the mortuary, "the success rate for families of the deceased in the two individual cases is zero percent." The investigation termed this "mission failure."

The Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians continue to question the county's actions.

A Los Angeles Times editorial recently called on county officials to follow through on a pledge to allow all groups claiming Ancestors to hold ceremonies at the site, "even if it means 100 ceremonies over 100 days."

Provide interpretive elements about the Native Americans and Pobladores buried at the site

Unite people around these principles and goals and bridge differences

Andy Salas ©

CLICK HERE